Members of the Arlington Baths Club have many amazing hobbies but we were particularly intrigued by what Dr James Duncanson got up to in his spare time.

James Gray Duncanson was born on 27 May 1871, about two months before we opened our doors. He was born at Auchingramont United Presbyterian Manse, in Hamilton, the son of the Reverend Peter Cunningham Duncanson and Jane Brown Gray Duncanson.

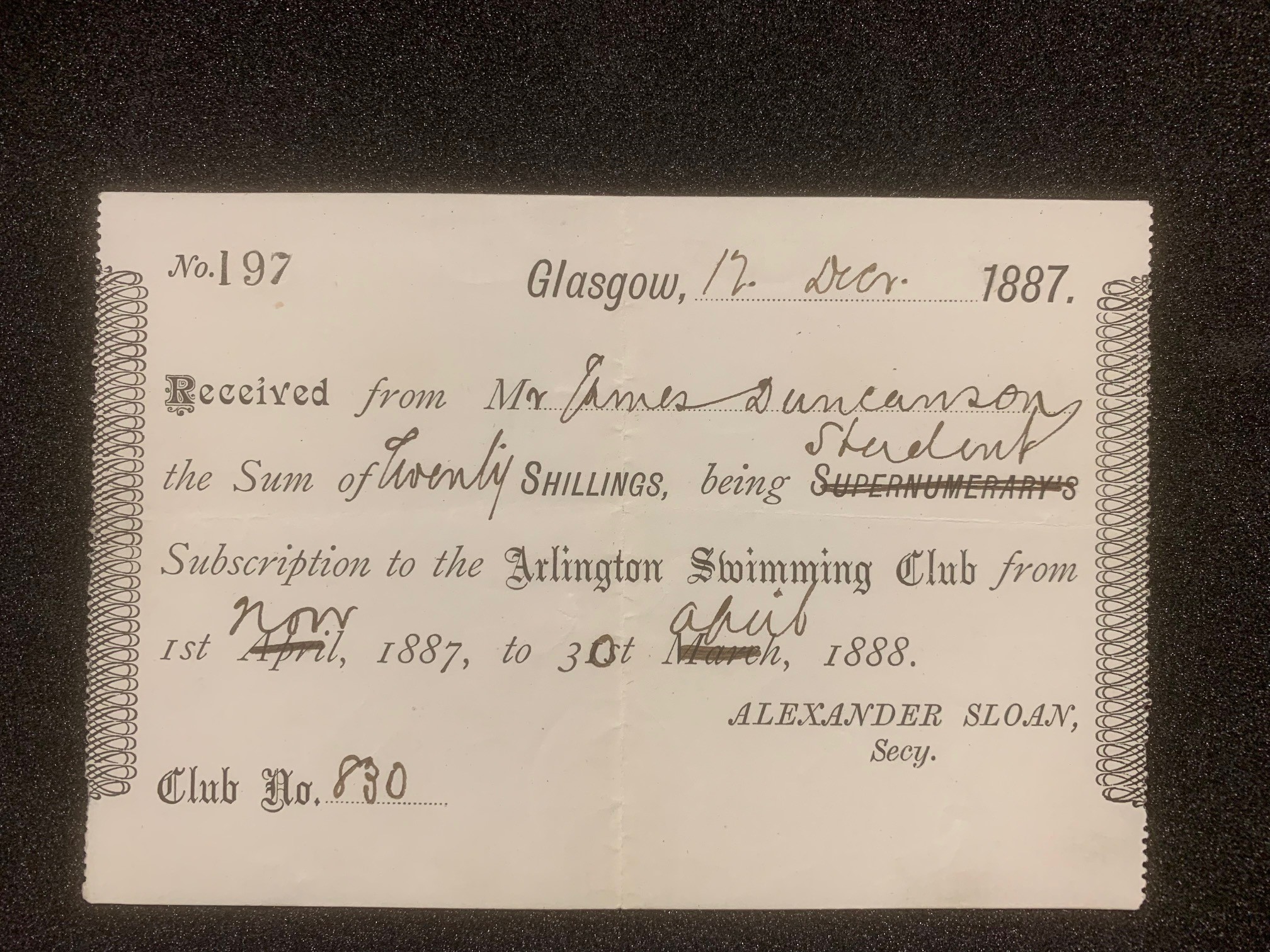

He went on to study medicine at the University of Glasgow in the late 1880s, which is when he joined the Baths.

After university James was a medical officer on a merchant navy ship and then joined the HMS Wellesley which was used as a training vessel. In 1893 he was appointed Senior Assistant Resident Medical Officer in the Victoria Infirmary.

His brother, John Cunningham Duncanson, was also a doctor with a practice in the Woolwich, Shooter’s Hill and Blackheath district in London. James joined him there in 1894 and it was here he developed his interests in photography including this striking portrait of Dougall the bulldog.

John Duncanson was six years older than James; as yet we have no record of him being a member while studying medicine. But, as well as being a medic he also had a very strange hobby – dog mesmerism!

In this beautiful photo from November 1909 James captures Dougall in a hypnotic trance after he has been mesmerized by John.

According to Wikipedia’s history of hypnosis, “modern-day hypnosis started in the late 18th century and was made popular by Franz Mesmer, a German physician who became known as the father of ‘modern hypnotism’. Hypnosis was known at the time as ‘Mesmerism’ being named after Mesmer.” Mesmer believed in the existence of a magnetic force which affected the health of the human body which he named ‘animal magnetism’.

In the 19th century Scottish surgeon James Braid (1795-1860) developed new ideas about hypnosis. He rejected the supernatural ideas of Mesmer but experimented and observed the effects of physiological and psychological processes such as suggestion and focused attention – visual fixation on a small bright object held eighteen inches above and in front of the eyes. He published academic and popular works on his ideas and experiments, including Observations on trance, or, Human hybernation in 1850 and and is still remembered today by the James Braid Society, an organisation for hypnotherapists.

In late Victorian and Edwardian periods, another Scottish physician kept Braid’s research in public view. John Milne Bramwell (1852-1925) beame interested in Braid’s work as a medical student at Edinburgh University. In 1890 he gave a public demonstration in Leeds of the use of hypnotism for dental and surgical anæsthesia which was reported in medical journals including The Lancet. He continued to research, demonstrate and write about hypnotism for therapeutic and medical treatment and in 1903 published Hypnotism: Its History, Practice and Theory, which was popular enough to run to a 3rd edition by 1913.

Is it possible that this book was what inspired the Duncanson doctors to practice their hypnotism skills on Dougall?

With the outbreak of World War I in 1914, James joined the Royal Army Medical Corps and became officer in charge of the medical division in the Auxiliary Hospital, Woolwich and the Royal Herbert Hospital. James would later be deployed to the No.72 General Hospital, Deauville, France. In France he rose to the rank of major and was mentioned in dispatches twice.

During this time he continued his interest in photography and the Imperial War Museum holds an extensive collection of 71 photographs taken by James. Sadly none of these are currently digitised.

After the end of the war James held the positions of Regional Medical Officer at the Ministry of Health, Secretary and Vice-President of the Therapeutical Section of the Royal Society of Medicine, and for some years he was a member of the National Formulary Subcommittee of the Insurance Acts Committee. He was also a medical referee for the Miners’ Phthisis Board Union South Africa. He died on 24 June 1933.

Researcher: Will

References:

- University of Glasgow Archive Services: Receipt for twenty shillings for student subscription to the Arlington Swimming Club, Glasgow, 12 Dec 1887, GB 248 UGC 140/8, Papers of James Gray Duncanson, 1871-1933, medical graduate, University of Glasgow.

- The National Archives: ‘Photograph of head of bull dog ¾ view (‘Dougall’)

- The National Archives: Photograph of bull dog mesmerised by Dr J C Duncanson

- Imperial War Museum: Collection – DUNCANSON JAMES GRAY (MAJOR)

- Internet Archive: Hypnotism: Its History, Practice and Theory

- Internet Archive: Human Magnetism; or, How to Hypnotise: A Practical Handbook for Students of Mesmerism

- The National Archives: ‘Photograph of head of bull dog ¾ view (‘Dougall’)

- The National Archives: Photograph of bull dog mesmerised by Dr J C Duncanson

- University of Cambridge – Chettiar T. ‘Looking as little like patients as persons well could’: hypnotism, medicine and the problem of the suggestible subject in late nineteenth-century Britain’. Medical History, July 2012, 56 (3), 335-54

- Wellcome Collection: Observations on trance, or, Human hybernation

- University of Glasgow Archive Services: Receipt for twenty shillings for student subscription to the Arlington Swimming Club, Glasgow, 12 Dec 1887. Papers of James Gray Duncanson, 1871-1933, medical graduate, University of Glasgow. GB 248 UGC 140/8

- Wikipedia: History of hypnosis

- Wikipedia: James Braid

- Wikipedia: John Milne Bramwell